The Price of Paradise

The French explorer Bougainville called them the “dangerous archipelago,” a name that echoes with the ghosts of old sailing ships. Before we arrived, I saw it as a romantic holdover. Now, as we point our bow north-east, back towards the safety of the Marquesas, I know better. The ghosts are real. They are the steel hulls and broken masts we encountered, but they are also the bleaching coral and the rising sea. They are the sudden gales and ripping currents.

The warnings first came in whispers across the cruiser networks and then came closer and closer. A boat had sunk in the Marquesas before we had come south.

Then a French family, their son not much younger than Nico, lost their catamaran after hitting what was most likely a submerged container, only two nights out from the Marquesas. Ironically, we had met them on a shore excursion at the island of Ua Pou shortly beforehand. The story we heard had them jump onto their paddleboard with their EPIRB in hand which fortunately helped them get rescued within hours.

A few days later, in the next bay along, at the main port of the island, we found a familiar boat lying sick on shore. Olivier, a fellow ‘inmate’ from the grimy Mexican boatyard where we’d spent months, had his boat washed ashore while he was on a day walk. Now he was soliciting funds online to raise money so the boat could be salvaged and authorities would permit him to depart. That had happened only a month before we got there.

We soon met one of them in person. Peter, a friendly Austrian sailor, was stranded in Fakarava. A broken anchor chain in the night sent his boat onto the reef, shredding his rudder. Weeks later when we left, he was still there, a prisoner of paradise, waiting on a salvage boat and the slow grind of insurance.

Then, the ghost came to visit us. Tied to a mooring at the other end of the Fakarava lagoon, a southerly gale descended. All night the boat strained. Around 5 a.m., a sickening jolt, and the wind shrieked through the rigging. The mooring line had snapped. Adrenaline, a roaring engine, and a frantic few minutes in the dark were all that separated us from the reef.

And on our last day in the atoll, we saw evidence of another ghost. A mast sticking rigidly out of the turquoise water, but at an odd angle. A sloop, dragged onto a reef two nights before. The crew was safe. Their home was gone, as we found out on WhatsApp.

An Intoxicating Beauty

Like playing Russian Roulette

This place is strange. It is, without question, the postcard paradise that attracts cruisers like us. Our arrival at Raroia atoll was pure magic. We threaded the needle of the pass at slack tide, slipping from the turbulent open ocean into a lagoon of impossible turquoise.

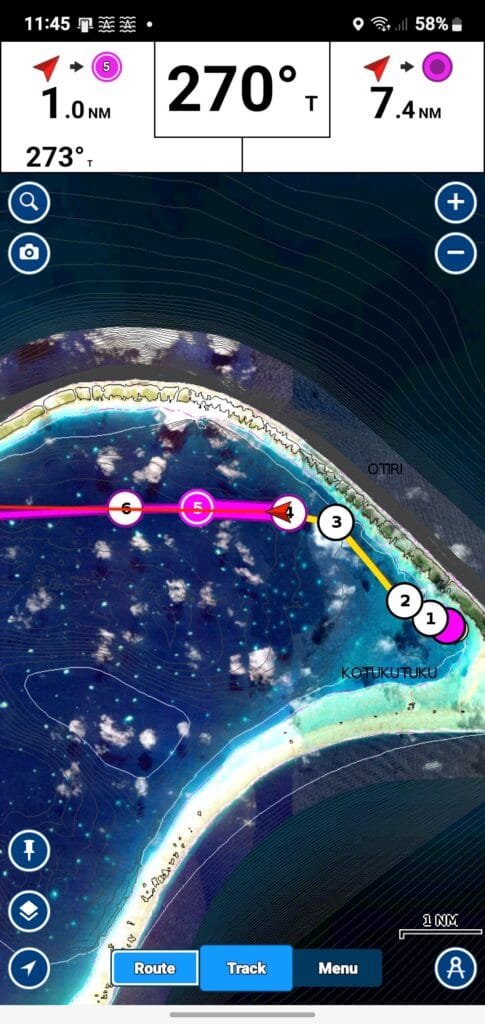

But the passes open into playing Russian Roulette with your boat. Typically studded with countless coral bommies, from 5 to 50 metres in diameter, these are invisible to the eye if you don’t have the sun in your back and sea state is not too agitated. Sure, there are satellite images available on boater’s chart plotters, but more often than not, there is cloud in the way along your route.

Timing and sharp lookout still leave enough risk for adrenaline running. And even then it can go wrong, as our friends on Salish Dragon discovered in another atoll around that time. Fortunately a good helping of Splash Zone, an underwater epoxy they had on board, saved their boat.

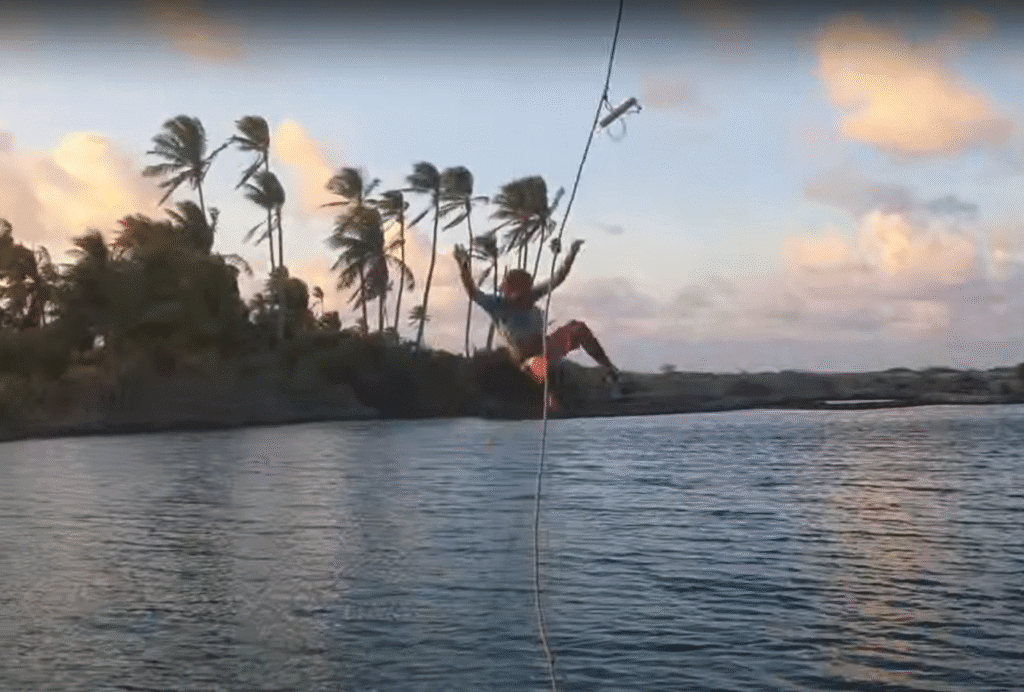

So after waiting to have the sun behind us, we carefully followed a recommended route using Google satellite images to wind our way through the coral bommies, barely visible at short distance. But waiting for us was that postcard anchorage with old and new friends that we then shared an idyllic fortnight with, snorkeling in crystal clear water, swinging of coconut trees and beach fires under a thousand stars.

It’s easy to get lost in the isolation of a remote lagoon. But the atolls aren’t just about survival and turquoise water; they are about people. Our next stop, Makemo, quickly pulled us out of our bubble and into the beating heart of a community.

Life on the Wharf

Life in the atolls, we soon learned, may appear tranquil in those secluded bays but it comes to life on the village wharf. In Makemo, the next atoll, we tied up along with several other boats that had departed Raroia with us and were instantly absorbed into the village rhythm. The day started with 5:30 a.m. church bells and the communal walk to the bakery. The air along the way smelled of bougainvillea, salt, and baking bread.

From our deck, we watched fishermen land their catch while Nico, along with other children, leaped from the boat, snorkeling among lemon sharks and a majestic, slow-moving giant Napoleon wrasse that patrolled beneath us.

Nico soon befriended local children. One older girl that took him home had already visited New Zealand. Pehevai was the daughter of Maruio who had just opened a new restaurant on the seaward side of the village. He showed us a spectacular YouTube video of his daughter singing on a remote islet in the same atoll (link at end of this post). Pehevai had represented French Polynesia at Pasifika, a regional cultural festival organised annually in Auckland. One night at the restaurant she agreed to sing just for us.

A few days later we found our way to the filming location and had a rare evening to ourselves at this romantic shoreline without another boat in sight – nor another person for that matter. But the fortnightly supply ship was due so we returned to town again soon.

To cloud the idyllic life a little, a front tooth crown I’d cracked in the Marquesas gave way completely. A dental emergency here seemed like a cruel joke. But the archipelago provides. An evening conversation on the wharf with a French woman named Emily, who was watching with us divers filet their catch, revealed she was a dentist on sabbatical. The next day, I had a new, temporary front tooth. “Just don’t eat any apples until you get back home and get an implant,” she warned.

On our last night in Makemo, we invited Emily, Maruio and his daughters to the wharf where we served up a candle-lit dinner under the stars as a thank you to our new friends.

The World Beneath

The underwater world is simply sublime, but it tells a complicated story. Diving Fakarava’s famous north pass was a sharp lesson in ecological contrast. The current carried us down into a theater of the wild: a wall of thirty or more grey reef sharks, hanging motionless, watching us with an ancient, unnerving calm. It was a sign of a healthy ecosystem, the apex predators in their rightful place.

But paradise is fragile. On another snorkel, Marea surfaced with a crown-of-thorns starfish, its venomous spines a grim confirmation that the invasive species had reached this atoll. When she showed it to the local dive masters, they nodded earnestly. They knew the danger—that the starfish are best exterminated in-situ with vinegar injections, because cutting them up only causes them to reproduce. Once this pest arrives, the reefs are doomed. The vibrant coral gardens we had just marveled at were living on borrowed time.

The Promise of Return

It was during that last crossing of the Fakarava lagoon, after seeing the wreck, that everything crystallized. The plan had always been to return to the Marquesas for the cyclone season, but seeing that mast, thinking of Peter’s shredded rudder, the doomed coral, and our own snapped mooring line—it confirmed the absolute wisdom of that plan. There was no debate, only a profound sense of relief.

Turning the boat east, back the way we came, felt like the most natural thing in the world. It wasn’t a retreat; it was the next logical step in a much longer journey. The Tuamotus test you, and we left with a deep respect for their power. But more than that, we left with a sense of immense gratitude—for the friends we’d made, for the beauty we’d witnessed, and for the lessons we’d learned.

As we sail north-east, the feeling on board is one of joyful anticipation. We look forward to seeing the familiar, soaring peaks of the Marquesas rise from the horizon again, to revisiting friends in those high, safe valleys. And we are already planning our return. We will be back next year to sail among the ghosts again, this time wiser, more prepared, and eager to discover new, delightful places and people in this dangerous, beautiful archipelago.

Post script:

The story took another turn after I drafted this. We never managed to find a weather window to get us back in time for the flight home for Marea and Nico we had booked from the Marquesas. So after several hiccups they managed to get a flight back to Papeete in time for the connection to Auckland – just not from Makemo as booked but Raroia insead, a rushed overnight sail away .

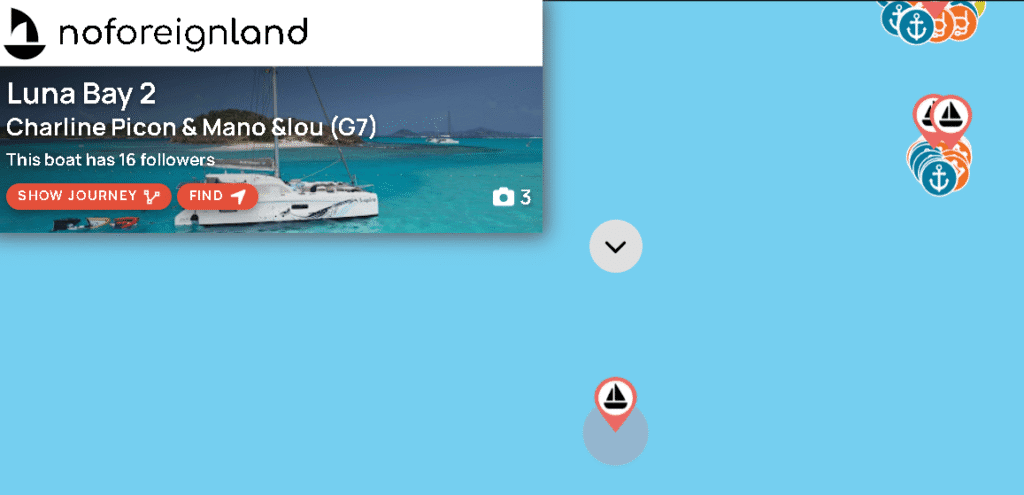

That left me to sail North by myself, which took a week. I did not see a single boat or ship during this time, nor on the radar. But on day 5 I noticed that I was approaching the position of a sailing boat plotted on the NoForeignLand app. But mysteriously it never came into sight, even though I must have passed over the marked position. It was only afterwards that Marea pointed out that was the last position of Luna 2, the catamaran with a child on board that had probably hit a container. The hull was never recovered and is still floating out there somewhere …

Not counting the boats that had run onto reefs or got pushed onto shore, there were 5 sinkings of foreign pleasure craft reported in French Polynesia this sailing season. That is 5 times the average with no clear explanation why. I tell yar all – there be ghosts out there!

PSS: On NoForeignLand, Luna Bay 2 remains as a ghost just 80 miles south east of Ua Pou Island.

You can find Pehevai on YouTube here. This is the song recorded at the filming location we visited: